What was the greatest invention of all time? The printing press? The wheel? The microchip? Now personally, I’m a big fan of the sofa, but I realize that without the invention of the remote control the sofa would not be the haven it is today. Some would say, however, that there is another invention which was more important than any of these, an invention without which none of the others would have been possible. An invention, in fact, that made mankind, rather than the other way around.

That invention was cooking. Clearly this required the discovery of fire beforehand, but since fire existed long before any proto-human figured out how to use it, I’m not counting it in the ‘invention’ category. Things have been catching fire on Earth for as long as there has been enough oxygen in the atmosphere to support combustion (there isn’t, by the way a simple answer as to how much oxygen that requires, since even a given material will require different concentrations of oxygen to burn depending on its shape, how finely divided the particles are, and a host of other factors).

Humans may have harnessed fire, but we can’t claim to have invented it. Cooking on the other hand, is a use for fire which is purely human, if you’ll permit me a little latitude on what the definition of ‘human’ is. Anthropologists used to think that bipedalism was the key innovation that caused our ancestors to get smart. The theory went that once you are walking around on two feet with your hands free to carry things and make tools, a big brain was inevitable. But discoveries in the last 40 or so years that showed hominids were walking around on two feet for around two million years without any noticeable increase in brain size began to suggest that something else was necessary.

And scientists who studied human metabolism started to think they had an answer-meat. A big brain is extremely costly, metabolically speaking. Our brains take 25% of our bodies’ total energy budget. Considering we’re talking about a couple of pounds of cottage cheese that can’t move, make noise, or do much of anything physically, that’s a lot of calories to spend. It’s all worth it, of course, since without all that cottage cheese up there you wouldn’t be able to enjoy reading funfacts, but there is a big energetic cost to increasing brain size, and something has got to supply the energy. Meat is more energy-rich than vegetable matter, so a proto-human with access to meat could more easily ingest enough calories to feed a big hungry brain. The social cooperation necessary for weak humans to successfully hunt swift or dangerous prey was thought to provide the impetus for a more complicated social structure that required a big brain.

It’s a nice theory, but it runs into a bit of a problem with regard to the fossil record. It looks like hominids were eating significant quantities of meat 2.5-3 million years ago, but it took close to another million years before those Australopithecine pea-brains turned into the brainy Homo erectus. Also, there are plenty of other carnivores out there, even highly social carnivores with sophisticated hunting techniques that get along with pretty small brains.

What almost all carnivores do have in common is not big brains but big teeth. Meat may be high in calories, but eating the stuff isn’t all that easy and requires big strong sharp teeth that are notably lacking in the human mouth. Stone tools definitely would have been a help, but a stone axe ain’t exactly a Henckel steak knife. In those pre-Ginsu days, proper digestion of meat required a lot of chewing and some intense digestion, and digestion isn’t trivial, energetically speaking. A big part of the metabolic budget of most animals goes simply to keeping the digestive system humming along. Without getting that metabolic cost down, you’re simply not going to be able to spare the calories to do any serious thinking.

Richard Wrangham, a primatologist at Harvard, believes that the key development that made humans human was cooking. Cooked food takes a lot less effort to digest than raw food. First of all, cooking softens food, reducing the amount of chewing that needs to be done, as well as allowing for smaller teeth and jaw muscles which led to significant remodeling of the human skull. But just as crucially, cooked meat takes less effort to digest, because cooking breaks down proteins and starches, making them easier to turn into useful sugars and amino acids.

Wrangham, who has studied chimps for over thirty years, has done detailed studies of how quickly they can take in calories from the raw fruit and meat that makes up their diet. Even ignoring the energy cost of actually catching and killing prey, Wrangham discovered that if Homo erectus could ingest calories at the rate of a chimp, it would take 6 hours a day of solid chewing of meat to keep their brains and bodies functioning properly. When you throw plant matter into the mix, Homo erectus would have quickly run out of time to do anything but chew. But cooked food requires less chewing and less energy to digest, which means you can eat less, faster, leaving time for minor issues such as actually gathering the food, hunting the prey, making the tools you used for both, not to mention getting a bit of sleep and conceiving, birthing and raising a new generation of hominids.

Working with Stephen Secor, an expert on animal digestive systems, Wrangham studied the effect of cooking on the digestive system of pythons. The scientists fed pythons identical calories of meat, but in four different preparations-raw and untouched, raw and ground, cooked, and cooked and ground. Pythons don’t chew their food, so both the cooking and the grinding could have a significant impact on the energy required to digest. They determined that cooked meat reduced the energy required to digest by 13% versus raw and cooked ground meat required 23% less energy to process.

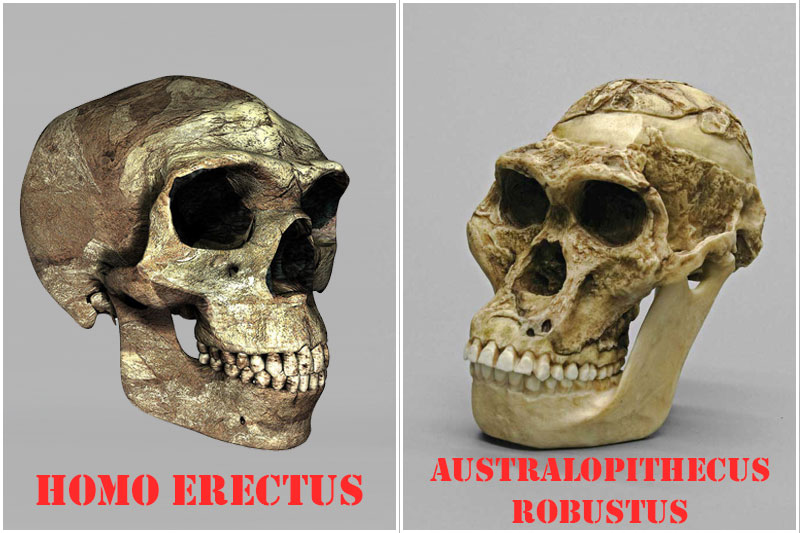

For Wrangham, the fact that the increase in brain size in hominids corresponds with a massive decrease in tooth size is a dead give-away that cooking was the key. Cooking would have given Homo erectus enough spare energy to feed that big brain, as well as requiring much less impressive dentition. Check out the skull of Homo erectus, versus its contemporary (but not our direct ancestor) Australopithecus robustus below it.

The braincase is the most obvious feature on H. erectus, but A. robustus is all about the jaw. That funny peak on top of the skull is actually the sagittal crest that the giant jaw muscles attach to.

Not all scientists agree with the cooking hypothesis, however. While there is some evidence associating H. erectus with fire, the earliest stone hearths date only to around 250,000 years ago, 1.5 million years after H. erectus came on the scene. For my part, though, I’m convinced. I refuse to believe my ancestors spent a million years futzing around with a metabolic energy excess before they wised up and grew a bigger brain. And as for the lack of evidence for hearths, I say it isn’t such a big deal. As I look around my kitchen, there isn’t a stone hearth anywhere, and you don’t see me spending my whole day chewing.