Once upon a time, the nearsighted among us had little choice but to squint if they wanted to see clearly at any distance. Those of you who know that our word for nearsightedness comes from the Greek meaning, more or less, to squint. It wasn’t until the 13th century that anyone came up with a better solution than squinting. This solution, of course, was eyeglasses.

There have been improvements to eyeglasses over the years – Ben Franklin’s invention of bifocals in the 18th century, the invention of contact lenses in the late 19th century, and the invention in the 1970’s of those oh so groovy photochromic glasses that spare their wearers from the indignity of having to switch to sunglasses when they go outside.

But all of these methods still require their users to wear something on their eyes when they want to see straight. It took a farsighted (sorry) ophthalmologic surgeon to realize that if you changed a patient’s eyes, you could do away with prosthetic vision enhancers altogether.

Refractive surgery

The solution was refractive surgery. Refractive surgery is a type of procedure intended to correct vision problems such as myopia and astigmatism. There are actually quite a number of different techniques, he most widely known of which is called LASIK. LASIK is short for laser assisted in-situ keratomileusis, and probably should win some award for world’s most necessary acronym. The idea behind all sorts of refractive eye surgery is that by changing the shape of the cornea, you can create a built-in corrective lens.

Basic techniques of eye surgery

While we think of such surgery as a recent development, the basic techniques were invented way back in the 1950’s by Jose Barraquer, an ophthalmologist working in Bogota, Colombia. Barraquer invented a device called a microkeratome, which is capable of slicing off a thin slice of the cornea. His technique involved removing a slice of cornea, freezing it and then shaping the frozen slice with a very accurate lathe.

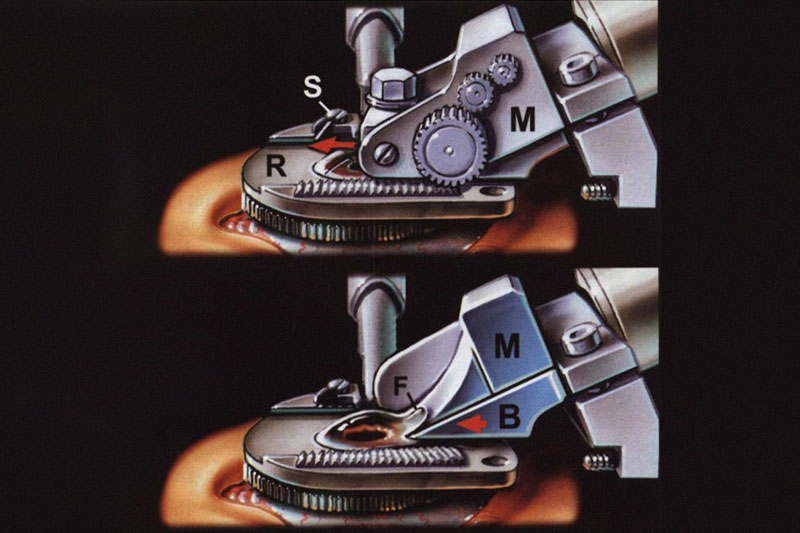

Most of the images of the process are pretty gross, but here is an illustration that isn’t so bad since it isn’t actually a photograph. You can see the cornea flap being sliced at F.

Microkeratome – Lasik Eye Surgery Instrument

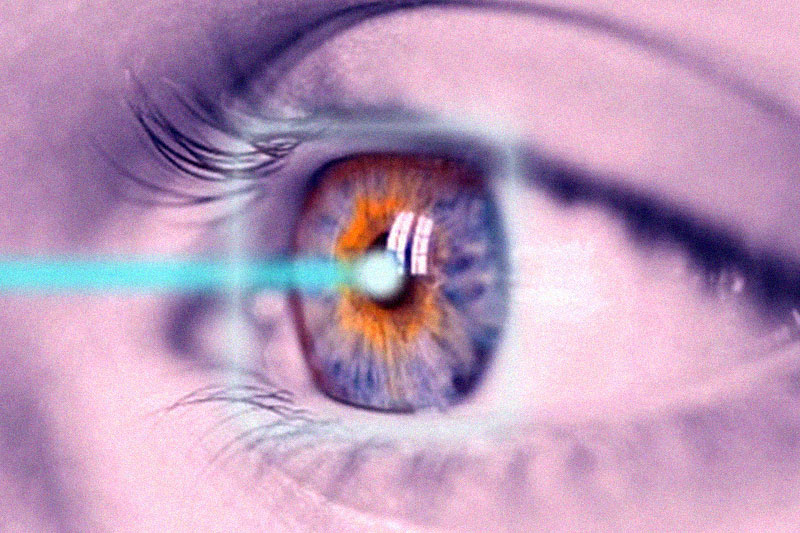

While Barraquer’s technique involved messing with the slice of cornea that is removed by the microkeratome, LASIK just peels back the curved upper area so the surgeon can mess with the resulting flat corneal surface. This is done with an excimer laser, which uses ultraviolet light to vaporize tissue without affecting the area around it (much).

Lasik Surgery Principle

In principle, this is a fairly simple matter. Eyeglass prescriptions are described in diopters, which specify the refractive errors of the eye. If your eye has a distance diopter of 2, then using a lens with a diopter of -2 (a concave lens with a negative radius of curvature) will get you to a nice focused 0. In LASIK, the ophthalmologist creates that -2 lens by carving pieces from your cornea.

Lasik Surgery in practice

In practice, life gets trickier. For one thing, everyone’s eyes contain subtle flaws which distort vision beyond the simple nearsighted/farsighted continuum.

Astigmatism is a condition in which the refractive power of the eye is different in the vertical axis than the horizontal, but there are all sorts of higher order aberrations (HOAs) which affect our vision.

These are a bit tougher to describe than the lower order aberrations like myopia, and have less than helpful descriptions such as coma, trefoil, and spherical aberration. There are in principle an infinite number of higher order aberrations, which are collectively described with something called Zernike polynomials-named after a Dutch physicist with an obsession for really good optics. Early refractive surgery had a tendency to substantially magnify HOAs.

A small but significant percentage of patients wound up with vision artifacts collectively referred to by ophthalmologists as GASH– short for Glare, Arc, Starburst, and Halo.

Not Good Candidates for LASIK

Problems with night vision are the most prevalent side-effect from refractive surgery because as the pupil expands in low light conditions, light begins to enter from parts of the cornea beyond the treated area-or at least beyond the optimally treated area.

For this reason, people with particularly large pupils are not good candidates for LASIK. But over time the frequency of these problems has fallen to well below 1% (at least according to ophthalmologists-those who like to see conspiracies claim that ophthalmologists are not exactly unbiased here).

But assuming the AMA hasn’t gotten to the military, the fact that US armed forces is a big proponent of the surgery suggests that they believe they are getting better soldiers out of it.

Refractive surgery improvements

Among the more important recent improvements to refractive surgery is the ability to help with HOA problems. This comes at a couple of different stages although the basic technique, wavefront analysis, is the same. Wavefront analysis involves a device entertainingly called an aberrometer that sends a beam of light with a particular pattern into the eye and analyzes the reflection coming back from the retina.

The instrument can then back out what aberrations are stopping the eye from reflecting the image back perfectly. When used diagnostically, wavefront analysis can tell whether a patient is a good candidate for surgery or not. Since refractive surgery tends to increase HOAs, a patient who already has a significant amount of trouble in that area may be a bad candidate for refractive surgery generally.

Wavefront-assisted LASIK

Those with less extreme but still significant HOA problems may be better candidates for wavefront-assisted LASIK or ‘custom’ LASIK. This involves another round of wavefront analysis, where the output is used to program the excimer laser to make a detailed burn pattern which attempts to undue as much of the HOAs as possible.

Even custom LASIK cannot eliminate all HOAs, and, in fact, will invariably create some new ones. Other negatives with the procedure relative to standard LASIK are higher cost, a greater amount of tissue removal (a potential problem for those with thin corneas) and a generally slightly smaller treatment area (a potential problem for those with big pupils). But on the other hand, the concept of a femtosecond laser-one with a beam duration measured in quadrillionths of a second-zooming around your cornea cutting out microscopic bits of your eye to help you see better certainly sounds pretty high tech.

Is LASIK Eye Surgery right for you?

So is LASIK surgery right for you? I haven’t the faintest idea. This is definitely one of those cases where only your doctor can tell you for sure, but prime candidates are generally considered those between 18-40 with a stable prescription, pupils that don’t get excessively large in low light, low or moderate levels of HOAs, and no complicating medical factors such as diabetes or autoimmune diseases.

Oh, and a fairly large wallet might be handy, too, since the procedure generally costs from $1000-$3000 per eye. You didn’t think that a procedure involving terms like keratomileusis, femtosecond lasers, and Zernike polynomials was going to come cheap, did you?